Einstein’s Entanglement: Bell Inequalities, Relativity, and the Qubit, by William Stuckey, Michael Silberstein and Timothy McDevitt, Oxford University Press

Quantum entanglement is the quantum phenomenon par excellence. Our world is a quantum world: the matter that we see and touch is the most obvious consequence of quantum physics and it wouldn’t really exist the way it is in a purely classical world. However, in our modern parlance when we talk about quantum sensors or quantum computing, what makes these things “quantum” is the employment of entanglement. Entanglement was first discussed by Einstein and Schrödinger, and later became famous with the celebrated EPR (Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen) paper of 1935.

Quantum entanglement is the quantum phenomenon par excellence. Our world is a quantum world: the matter that we see and touch is the most obvious consequence of quantum physics and it wouldn’t really exist the way it is in a purely classical world. However, in our modern parlance when we talk about quantum sensors or quantum computing, what makes these things “quantum” is the employment of entanglement. Entanglement was first discussed by Einstein and Schrödinger, and later became famous with the celebrated EPR (Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen) paper of 1935.

The magic of entanglement

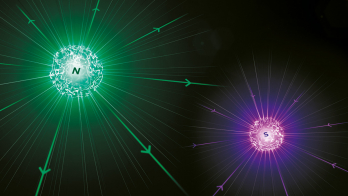

In an entangled particle system, some properties have to be assigned to the system itself and not to individual particles. When a neutral pion decays into two photons, for example, conservation of angular momentum requires their total spin to be zero. Since the photons travel in opposite directions in the pion’s rest frame, in order for their spins to cancel they must share the same “helicity”. Helicity is the spin projection along the direction of motion, and only two states are possible: left- or right-handed. If one photon is measured to be left-handed, the other must be left-handed as well. The entangled photons must be thought of as a single quantum object: neither do the individual particles have predefined spins nor does the measurement performed on one cause the other to pick a spin orientation. Experiments in more complicated systems have ruled these possibilities out, at least in their simplest incarnations, and this is exactly where the magic of entanglement begins.

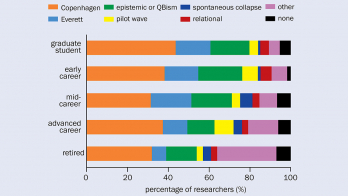

Quantum entanglement is the main topic of Einstein’s Entanglement by William Stuckey, Michael Silberstein and Timothy McDevitt, all currently teaching at Elizabethtown College, Pennsylvania. The trio have complementary expertise in physics, philosophy and maths, and this is not their first book on the foundations of physics. They aim to explain why entanglement is so puzzling to physicists and the various ways that have been employed over the years to explain (or even explain away) the phenomenon. They also want to introduce the readers to their own idea on how to solve the riddle and argue about its merits.

Why is entanglement so puzzling to physicists, and what has been employed to explain the phenomenon?

General readers may struggle in places. The book does have accessible chapters, for example one at the start with a quantum-gloves experiment – a nice way to introduce the reader to the problem – as well as a chapter on special relativity. Much of the discussion about quantum mechanics, however, uses advanced concepts such as Hilbert space and the Bloch sphere, that belong to an undergraduate course in quantum mechanics. Philosophical terminology, such as “wave-function realism”, is also used copiously. The explanations and the discussion provided are of good quality and an interested reader in the interpretations of quantum mechanics with some background in physics has a lot to gain. The authors quote copiously from a superb list of references and include many interesting historical facts that make reading the book very entertaining.

In general, the book criticises constructive approaches to interpreting quantum mechanics that explicitly postulate physical phenomena. In the example of neutral-pion decay that I gave previously, the case in which the measurement of one photon causes the other photon to pick a spin would require a constructive explanation. These can be contrasted with principle explanations, which may involve, for example, invoking an overarching symmetry. To quote an example that is used many times in the book, the relativity principle can be used to explain Lorentz length contraction without the need for a physical mechanism to contract the bodies, which would require a constructive explanation.

The authors make the claim that the conceptual issues with entanglement can be solved by sticking to principle explanations and, in particular, with the demand that Planck’s constant is measured to be the same in all inertial reference frames. Whether this simple suggestion is adequate to explain the mysteries of quantum mechanics, I will leave to the reader. Seneca wrote in his Natural Questions that “our descendants will be astonished at our ignorance of what to them is obvious”. If the authors are correct, entanglement may prove to be a case in point.