A report from the CMS experiment.

In particle physics, searches for new phenomena have traditionally been guided by theory, focusing on specific signatures predicted by models beyond the Standard Model. Machine learning offers a different way forward. Instead of targeting known possibilities, it can scan the data broadly for unexpected patterns, without assumptions about what new physics might look like. CMS analysts are now using these techniques to conduct model-independent searches for short-lived particles that could escape conventional analyses.

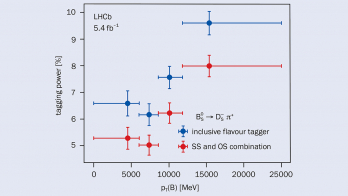

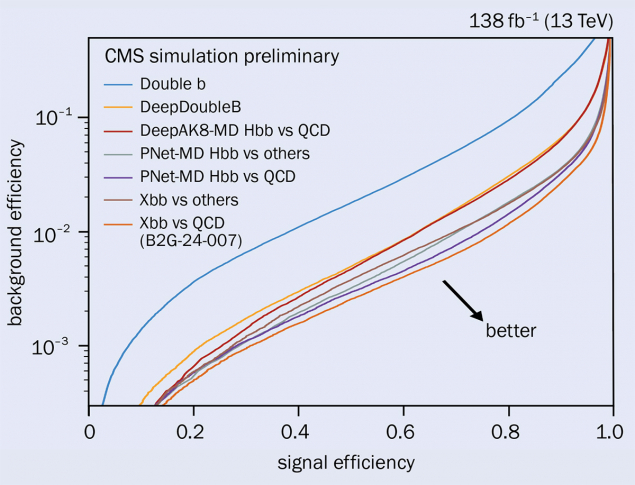

Dynamic graph neural networks operate on graph-structured data, processing both the attributes of individual nodes and the relationships between them. One such model is ParticleNet, which represents large-radius-jet constituents as networks to identify N-prong hadronic decays of highly boosted particles, predicting their parent’s mass. The tool recently aided a CMS search for the single production of a heavy vector-like quark (VLQ) decaying into a top quark and a scalar boson, either the Higgs or a new scalar particle. Alongside ParticleNet, a custom deep neural network was trained to identify leptonic top-quark decays by distinguishing them from background processes over a wide range of momenta. With this approach, the analysis achieved sensitivity to VLQ production cross-sections as small as 0.15 fb. Emerging methods such as transformer networks can provide even more sensitivity in future searches (see figure 1).

Another novel approach combined two distinct machine-learning tools in the search for a massive scalar X decaying into a Higgs boson and a second scalar Y. While ParticleNet identified Higgs-boson decays to two bottom quarks, potential Y signals were assigned an “anomaly score” by an autoencoder – a neural network trained to reproduce its input and highlight atypical features in the data. This technique provided sensitivity to a wide range of unexpected decays without relying on specific theoretical models. By combining targeted identification with model-independent anomaly detection, the analysis achieved both enhanced performance and broad applicability.

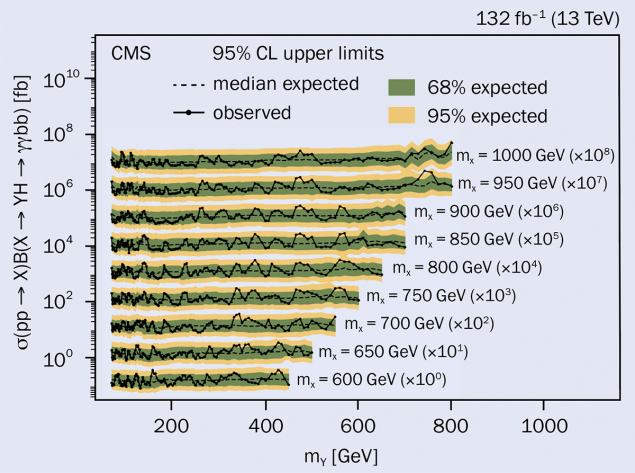

Searches at the TeV scale sit at the frontier where not only more and more data but also algorithmic innovation drives experimental discovery. Tools such as targeted deep neural networks, parametric neural networks (PNNs) – which efficiently scan multi-dimensional mass landscapes (see figure 2) – and model-independent anomaly detection, are opening new ways to search for deviations from the Standard Model. Analyses of the full LHC Run 2 dataset have already revealed intriguing hints, with several machine-learning studies reporting local excesses – including a 3.6σ excess in a search for V′ → VV or VH → jets, and deviations up to 3.3σ in various X → HY searches. While no definitive signal has yet emerged, the steady evolution of neural-network techniques is already changing how new phenomena are sought, and anticipation is high for what they may reveal in the larger Run 3 dataset.

Further reading

CMS Collab. CMS-PAS-B2G-23-009.

CMS Collab. CMS-PAS-B2G-24-015.