A report from the LHCb experiment.

The LHCb collaboration has developed a new inclusive flavour-tagging algorithm for neutral B-mesons. Compared to standard approaches, it can correctly identify 35% more B0 and 20% more B0s decays, expanding the dataset available for analysis. This increase in tagging power will allow for more accurate studies of charge–parity (CP) violation and B-meson oscillations.

In the Standard Model (SM), neutral B-mesons oscillate between particle and antiparticle states via second-order weak interactions involving a pair of W-bosons. Flavour-tagging techniques determine whether a neutral B-meson was initially produced as a B0 or its antiparticle B0, thereby enabling the measurement of time-dependent CP asymmetries. As the initial flavour can only be inferred indirectly from noisy, multi-particle correlations in the busy hadronic environment of the LHC, mistag rates have traditionally been high.

Until now, the LHCb collaboration has relied on two complementary flavour-tagging strategies. One infers the signal meson’s flavour by analysing the decay of the other b-hadron in the event, whose existence follows from bb– pair production in the original proton-proton collision. Since the two hadrons originate from oppositely-charged, early-produced bottom quarks, the method is known as “opposite-side” (OS) tagging. The other strategy, or “same-side” (SS) tagging, uses tracks from the fragmentation process that produced the signal meson. Each provides only part of the picture, and their combination defined the state of the art in previous analyses.

The new algorithm adopts a more comprehensive approach. Using a deep neural network based on the “DeepSets” architecture, it incorporates information from all reconstructed tracks associated with the hadronisation process, rather than preselecting a subset of candidates. By considering the global structure of the event, the algorithm builds a more detailed inference of the meson’s initial flavour. This inclusive treatment of the available information increases both the sensitivity and the statistical reach of the tagging procedure.

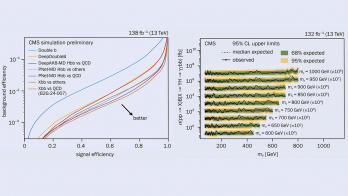

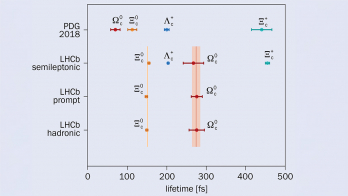

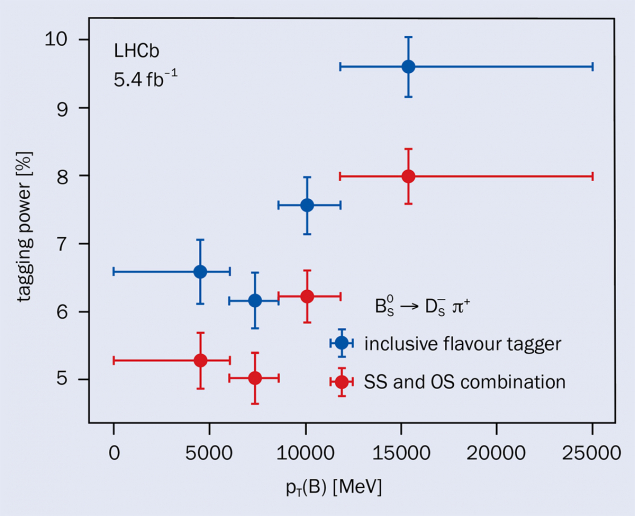

The model was trained and calibrated using well-established B0 and B0s meson decay channels. When compared with the combination of opposite-side and same-side taggers, the inclusive algorithm displayed a 35% increase in tagging power for B0 mesons and 20% for B0s mesons (see figure 1). The improvement stems from gains in both the fraction of events that receive a flavour tag and how often the tag is correct. Tagging power is a critical figure of merit, as it determines the effective amount of usable data. Therefore, even modest gains can dramatically reduce statistical uncertainties in CP-violation and B-oscillation measurements, enhancing the experiment’s precision and discovery potential.

This development illustrates how algorithmic innovation can be as important as detector upgrades in pushing the boundaries of precision. The improved tagging power effectively expands the usable data sample without requiring additional collisions, enhancing the experiment’s capacity to test the SM and seek signs of new physics within the flavour sector. The timing is particularly significant as LHCb enters Run 3 of the LHC programme, with higher data rates and improved detector components. The new algorithm is designed to integrate smoothly with existing reconstruction and analysis frameworks, ensuring immediate benefits while providing scalability for the much larger datasets expected in future runs.

As the collaboration accumulates more data, the inclusive flavour-tagging algorithm is likely to become a central tool in data analysis. Its improved performance is expected to reduce uncertainties in some of the most sensitive measurements carried out at the LHC, strengthening the search for deviations from the SM.