A report from the ATLAS experiment.

A defining yet unobserved property of the Higgs boson is its ability to couple to itself. The ATLAS collaboration has now set new bounds on this interaction, by probing the rare production of Higgs-boson pairs. Since the self-coupling strength directly connects to the shape of the Higgs potential, any departure from the Standard Model (SM) prediction would have direct implications for electroweak symmetry breaking and the early history of the universe. This makes its measurement one of the most important objectives of modern particle physics.

Higgs-boson pair production is a thousand times less frequent than single-Higgs events, roughly corresponding to a single occurrence every three trillion proton–proton collisions at the LHC. Observing such a rare process demands both vast datasets and highly sophisticated analysis techniques, along with the careful choice of a sensitive probe. Among the most effective is the HH → bbγγ channel, where one Higgs boson decays into a bottom quark–antiquark pair and the other into two photons. This final state balances the statistical reach of the dominant Higgs decay to bottom quarks with the exceptionally clean signature offered by photon-pair measurements. Despite the small signal branching ratio of about 0.26%, the decay to two photons benefits from the excellent di-photon mass resolution and offers the highest efficiency among the leading HH channels. This provides the HH → bbγγ channel with an excellent sensitivity to variations in the trilinear self-coupling modifier κλ, defined as the ratio of the measured Higgs-boson self-coupling to the SM prediction.

In its new study, the ATLAS collaboration relied on Run 3 data collected between 2022 and 2024, and on the full Run 2 dataset, reaching an integrated luminosity of 308 fb–1. Events were selected with two high-quality photons and at least two b-tagged jets, identified using the latest and most performant ATLAS b-tagging algorithm. To further distinguish signal from background, dominated by non-resonant γγ+jets and single-Higgs production with H → γγ, a set of machine-learning classifiers called “multivariate analysis discriminants” were trained and used to filter genuine HH → bbγγ signals.

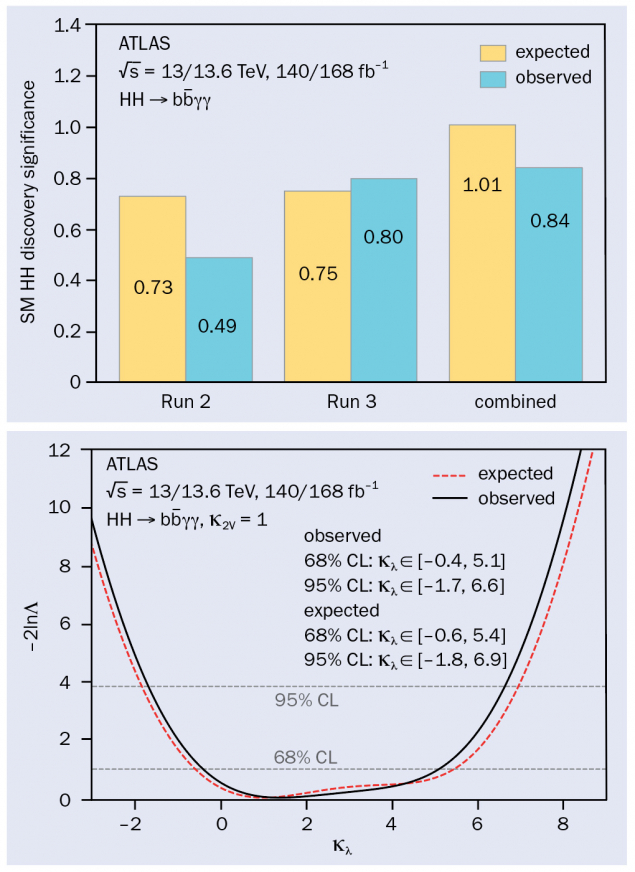

The collaboration reported an HH → bbγγ signal significance of 0.84σ under the background-only hypothesis, compared to a SM expectation of 1.01σ (see figure 1). At the 95% confidence level, the self-coupling modifier was constrained to –1.7 < κλ < 6.6. These results extend previous Run 2 analyses and deliver a substantially improved sensitivity, comparable to the observed (expected) significance of 0.4σ (1σ) in the combined Run 2 results across all channels. The improvement is primarily due to the adoption of advanced b-tagging algorithms, refined analysis techniques yielding better mass resolution and a larger dataset, more than double that of previous studies.

This result marks significant progress in the search for Higgs self-interactions at the LHC and highlights the potential of Run 3 data. With the full Run 3 dataset and the High-Luminosity LHC on the horizon, ATLAS is set to extend these measurements – improving our understanding of the Higgs boson and searching for possible signs of physics beyond the SM.