Herwig Schopper, Director-General of CERN from 1981 to 1988, passed away on 19 August at the age of 101. A brilliant scientist, manager and diplomat, Herwig set the course for CERN to become the pre-eminent laboratory for particle physics.

Herwig Schopper was born on 28 February 1924 in the German-speaking town of Landskron (today, Lanškroun) in the then young country of Czechoslovakia. He enjoyed an idyllic childhood, holidaying at his grandparents’ hotel in Abbazia (today, Opatija) on what is now the Croatian Adriatic coast. It was there that his interest in science was awakened through listening in on conversations between physicists from Budapest and Belgrade. In Landskron, he developed an interest in music and sport, learning to play both piano and double bass, and skiing in the nearby mountains. He also learned to speak English, not merely to read Shakespeare as was the norm at the time, but to be able to converse, thanks to a Jewish teacher who had previously spent time in England. This skill was to prove transformational later in life.

The idyll began to crack in 1938 when the Sudetenland was annexed by Germany. War broke out the following year, but the immediate impact on Herwig was limited. He remained in Landskron until the end of his high-school educ ation, graduating as a German citizen – and with no choice but to enlist. Joining the Luftwaffe signals corps, because he thought that would help him develop his knowledge of physics, he served for most of the war on the Eastern Front ensuring that communication lines remained open between military headquarters and the troops on the front lines. As the war drew to a close in March 1945, he was transferred west, just in time to see the Western Allies cross the Rhine at Remagen. Recalled to Berlin and given orders to head further west, Herwig instructed his driver to first make a short detour via Potsdam. This was a sign of the kind of person Herwig was that, amidst the chaos of the fall of Berlin, he wanted to see Schloss Sanssouci, Frederick the Great’s temple to the enlightenment, while he had the chance.

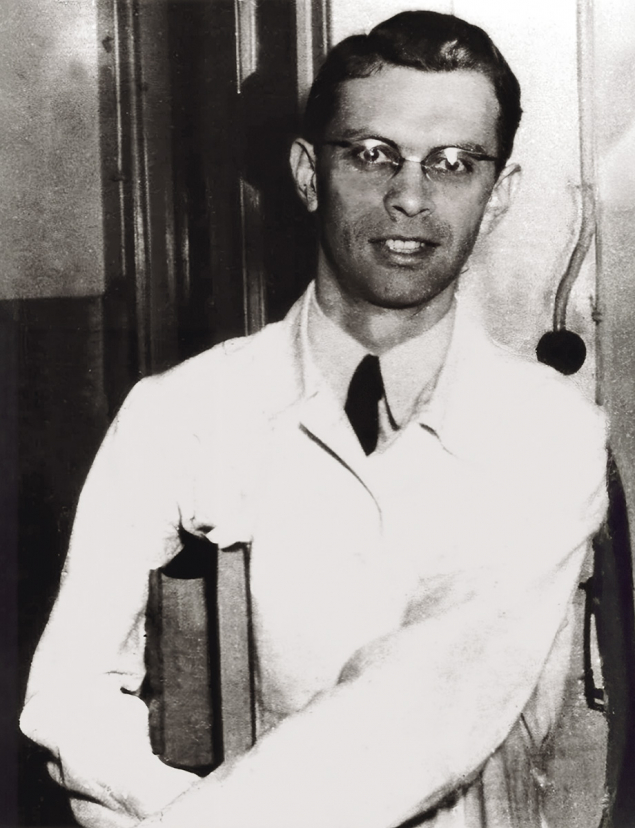

By the time Herwig arrived in Schleswig–Holstein, the war was over, and he found himself a prisoner of the British. He later recalled, with palpable relief, that he had managed to negotiate the war without having to shoot at anyone. On discovering that Herwig spoke English, the British military administration engaged him as a translator. This came as a great consolation to Herwig since many of his compatriots were dispatched to the mines to extract the coal that would be used to reconstruct a shattered Germany. Herwig rapidly struck up a friendship with the English captain he was assigned to. This in turn eased his passage to the University of Hamburg, where he began his research career studying optics, and later enabled him to take the first of his scientific sabbaticals when travel restrictions on German academics were still in place (see “Academic overture” image).

In 1951, Herwig left for a year in Stockholm, where he worked with Lise Meitner on beta decay. He described this time as his first step up in energy from the eV-energies of visible light to the keV-energies of beta-decay electrons. A later sabbatical, starting in 1956, would see him in Cambridge, where he worked under Meitner’s nephew, Otto Frisch, in the Cavendish laboratory. As Austrian Jews, both Meitner and Frisch had sought exile before the war. By this time, Frisch had become director of the Cavendish’s nuclear physics department and a fellow of the Royal Society.

Initial interactions

While at Cambridge, Herwig took his first steps in the emerging field of particle physics, and became one of the first to publish an experimental verification of Lee and Yang’s proposal that parity would be violated in weak interactions. His single-author paper was published soon after that by Chien-Shiung Wu and her team, leading to a lifelong friendship between the two (see “Virtuosi” image).

Following Wu’s experimental verification of parity violation, cited by Herwig in his paper, Lee and Yang received the Nobel Prize. Wu was denied the honour, ostensibly on the basis that she was one of a team and the prize can only be shared three ways. It remains in the realm of speculation whether Herwig would have shared the prize had his paper been the first to appear.

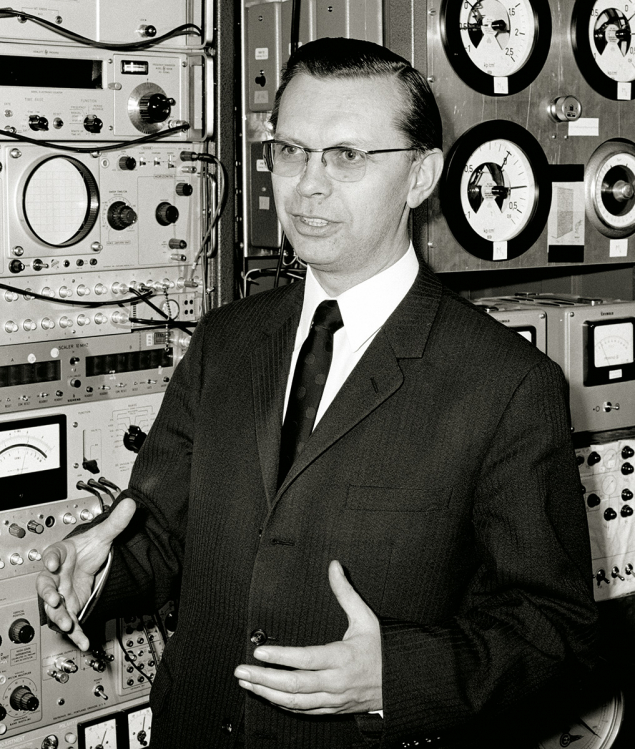

A third sabbatical, arranged by Willibald Jentschke, who wanted Herwig to develop a user group for the newly established DESY laboratory, saw the Schopper family move to Ithaca, New York in 1960. At Cornell, Herwig learned the ropes of electron synchrotrons from Bob Wilson. He also learned a valuable lesson in the hands-on approach to leadership. Arriving in Ithaca on a Saturday, Herwig decided to look around the deserted lab. He found one person there, tidying up. It turned out not to be the janitor, but the lab’s founder and director, Wilson himself. For Herwig, Cornell represented another big jump in energy, cementing Schopper as an experimental particle physicist.

Cornell represented another big jump in energy, cementing Schopper as an experimental particle physicist

Herwig’s three sabbaticals gave him the skills he would later rely on in hardware development and physics analysis, but it was back in Germany that he honed his management skills and established himself a skilled science administrator.

At the beginning of his career in Hamburg, Herwig worked under Rudolf Fleischmann, and when Fleischmann was offered a chair at Erlangen, Herwig followed. Among the research he carried out at Erlangen was an experiment to measure the helicity of gamma rays, a technique that he’d later deploy in Cambridge to measure parity violation.

It was not long before Herwig was offered a chair himself, and in 1958, at the tender age of 34, he parted from his mentor to move to Mainz. In his brief tenure there, he set wheels in motion that would lead to the later establishment of the Mainz Microtron laboratory, today known as MAMI. By this time, however, Herwig was much in demand, and he soon moved to Karlsruhe, taking up a joint position between the university and the Kernforschungszentrum, KfK. His plan was to merge the two under a single management structure as the Karlsruhe Institute for Experimental Nuclear Physics. In doing so, he laid the seeds for today’s Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, KIT.

Pioneering research

At Karlsruhe, Herwig established a user group for DESY, as Jentschke had hoped, and another at CERN. He also initiated a pioneering research programme into superconducting RF and had his first personal contacts with CERN, spending a year there in 1964. In typical Herwig fashion, he pursued his own agenda, developing a device he called a sampling total absorption counter, STAC, to measure neutron energies. At the time, few saw the need for such a device, but this form of calorimetry is now an indispensable part of any experimental particle physicists’ armoury.

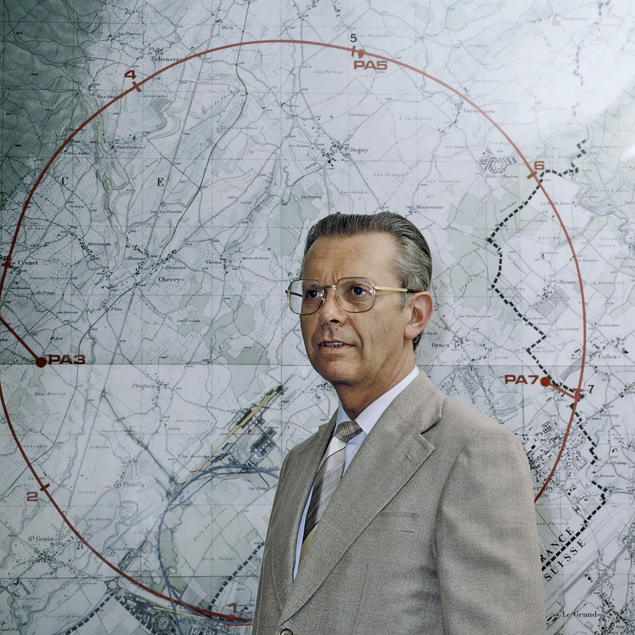

In 1970, Herwig again took leave of absence from Karlsruhe to go to CERN. He’d been offered the position of head of the laboratory’s Nuclear Physics Division, but his stay was to be short lived (see “Prélude” image). The following year, Jentschke took up the position of Director-General of CERN alongside John Adams. Jentschke was to run the original CERN laboratory, Lab I, while Adams ran the new CERN Lab II, tasked with building the SPS. This left a vacancy at Germany’s national laboratory, and the job was offered to Herwig. It was too good an offer to refuse.

As chair of the DESY directorate, Herwig witnessed from afar the discovery of both charm and bottom quarks in the US. Although missing out on the discoveries, DESY’s machines were perfect laboratories to study the spectroscopy of these new quark families, and DESY went on to provide definitive measurements. Herwig also oversaw DESY’s development in synchrotron light science, repurposing the DORIS accelerator as a light source when its physics career was complete and it was succeeded by PETRA.

The ambition of the PETRA project put DESY firmly on course to becoming an international laboratory, setting the scene for the later HERA model. PETRA experiments went on to discover the gluon in 1979.

The following year, Herwig was named as CERN’s next Director-General, taking up office on 1 January 1981. By this time, the CERN Council had decided to call time on its experiment with two parallel laboratories, leaving Herwig with the task of uniting Lab I and Lab II. The Council was also considering plans to build the world’s most powerful accelerator, the Large Electron–Positron collider, LEP.

It fell to Herwig both to implement a new management structure for CERN and to see the LEP proposal through to approval (see “Architects of LEP” image). Unpopular decisions were inevitable, making the early years of Herwig’s mandate somewhat difficult. In order to get LEP approved, he had to make sacrifices. As a result, the Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), the world’s only hadron collider, collided its final beams in 1984 and cuts had to be made across the research programme. Herwig was also confronted with a period of austerity in science funding, and found himself obliged to commit CERN to constant funding in real terms throughout the construction of LEP, and as it turns out, in perpetuity.

It fell to Herwig both to implement a new management structure for CERN and to see the LEP proposal through to approval

Herwig’s battles were not only with the lab’s governing body; he also went against the opinions of some of his scientific colleagues concerning the size of the new accelerator. True to form, Herwig stuck with his instinct, insisting that the LEP tunnel should be 27 km around, rather than the more modest 22 km that would have satisfied the immediate research goals while avoiding the difficult geology beneath the Jura mountains. Herwig, however, was looking further ahead – to the hadron collider that would follow LEP. His obstinacy was fully vindicated with the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012, confirming the Brout–Englert–Higgs mechanism, which had been proposed almost 50 years earlier. This discovery earned the Nobel Prize for Peter Higgs and François Englert in 2013 (see “Towards LEP and the LHC” image).

The CERN blueprint

Difficult though some of his decisions may have been, there is no doubt that Herwig’s 1981 to 1988 mandate established the blueprint for CERN to this day. The end of operations of the ISR may have been unpopular, and we’ll never know what it may have gone on to achieve, but the world’s second hadron collider at the SPS delivered CERN’s first Nobel prize during Herwig’s mandate, awarded to Carlo Rubbia and Simon van der Meer in 1984 for the discovery of W and Z bosons.

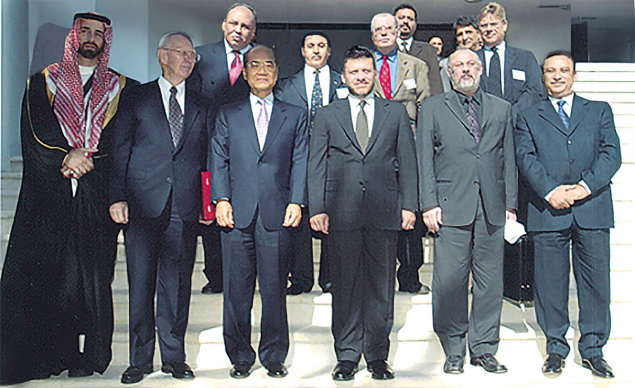

Herwig turned 65 two months after stepping down as CERN Director-General, but retirement was never on his mind. In the years that followed, he carried out numerous roles for UNESCO, applying his diplomacy and foresight to new areas of science. UNESCO was in many ways a natural step for Herwig, whose diplomatic skills had been honed by the steady stream of high-profile visitors to CERN during his mandate as Director-General. At one point, he engineered a meeting at UNESCO between Jim Cronin, who was lobbying for the establishment of a cosmic-ray observatory in Argentina, and the country’s president, Carlos Menem. The following day, Menem announced the start of construction of the Pierre Auger Observatory. On another occasion, Herwig was tasked with developing the Soviet gift to Cuba of a small particle accelerator into a working laboratory. That initiative would ultimately come to nothing, but it helped Herwig prepare the groundwork for perhaps his greatest post-retirement achievement: SESAME, a light-source laboratory in Jordan that operates as an intergovernmental organisation following the CERN model (see “Science diplomacy” image). Mastering the political challenge of establishing an organisation that brings together countries from across the Middle East – including long-standing rivals – required a skill set that few possess.

Although the roots of SESAME can be traced to a much earlier date, by the end of the 20th century, when the idea was sufficiently mature for an interim organisation to be established, Herwig was the natural candidate to lead the new organisation through its formative years. His experience of running international science coupled with his post-retirement roles at UNESCO made him the obvious choice to steer SESAME from idea to reality. It was Herwig who modelled SESAME’s governing document on the CERN convention, and it was Herwig who secured the site in Jordan for the laboratory. Today, SESAME is producing world-class research – a shining example of what can be achieved when people set aside their differences and focus on what they have in common.

Establishing an organisation that brings together countries from across the Middle East required a skill set few possess

Herwig never stopped working for what he believed in. When CERN’s current Director-General convened a meeting with past Directors-General in 2024, along with the president of the CERN Council, Herwig was present. When initiatives were launched to establish an international research centre in the Balkans, Herwig stepped up to the task. He never lost his sense of what is right, and he never lost his mischievous sense of humour. Following an interview at his house in 2024 for the film The Peace Particle, the interviewer asked whether he still played the piano. Herwig stood up, walked to the piano and started to play a very simple arrangement of Christian Sinding’s “Rustle of Spring”. Just as curious glances started to be exchanged, he transitioned, with a twinkle in his eye, to a beautifully nuanced rendition of Liszt’s “Liebestraum No. 3”.

Herwig Schopper was a rare combination of genius, polymath, humanitarian and gentleman. Always humble, he could make decisions with nerves of steel when required. His legacy spans decades and disciplines, and has shaped the field of particle physics in many ways. With his passing, the world has lost a truly remarkable individual. He will be sorely missed.