When targeting tumours, protons and heavy ions offer distinct advantages compared to conventional X-ray radiotherapy. PTCOG president Marco Durante describes an exciting future for the technology and shares his vision for closer international cooperation between medicine, academia and industry.

What excites you most about your research in 2025?

2025 has been a very exciting year. We just published a paper in Nature Physics about radioactive ion beams.

I also received an ERC Advanced Grant to study the FLASH effect with neon ions. We plan to go back to the 1970s, when Cornelius Tobias in Berkeley thought of using very heavy ions against radio-resistant tumours, but now using FLASH’s ultrahigh dose rates to reduce its toxicity to healthy tissues. Our group is also working on the simultaneous acceleration of different ions: carbon ions will stop in the tumour, but helium ions will cross the patient, providing an online monitor of the beam’s position during irradiation. The other big news in radiotherapy is vertical irradiation, where we don’t rotate the beam around the patient, but rotate the patient around the beam. This is particularly interesting for heavy-ion therapy, where building a rotating gantry that can irradiate the patient from multiple angles is almost as expensive as the whole accelerator. We are leading the Marie Curie UPLIFT training network on this topic.

Why are heavy ions so compelling?

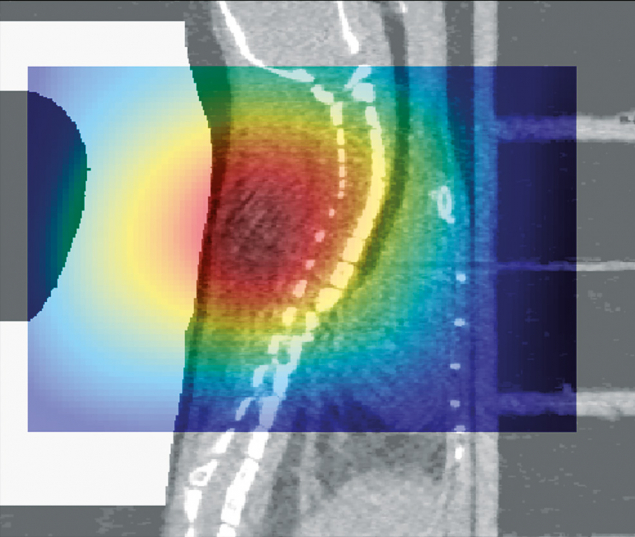

Close to the Bragg peak, where very heavy ions are very densely ionising, the damage they cause is difficult to repair. You can kill the tumours much better than with protons. But carbon, oxygen and neon run the risk of inducing toxicity in healthy tissues. In Berkeley, more than 400 patients were treated with heavy ions. The results were not very good, and it was realised that these ions can be very toxic for normal tissue. The programme was stopped in 1992, and since then there has been no more heavy-ion therapy in the US, though carbon-ion therapy was established in Japan not long after. Today, most of the 130 particle-therapy centres worldwide use protons, but 17 centres across Asia and Europe offer carbon-ion therapy, with one now under construction at the Mayo Clinic in the US. Carbon is very convenient, because the plateau of the Bragg curve is similar to X-rays, while the peak is much more effective than protons. But still, there is evidence that it’s not heavy enough, that the charge is not high enough to get rid of very radio-resistant hypoxic tumours – tumours where you don’t have enough oxygenation. So that’s why we want to go heavier: neon. If we show that you can manage the toxicity using FLASH, then this is something that can be translated into the clinics.

There seems to be a lot of research into condensing the dose either in space, in microbeams or, in time, in the FLASH effect…

Absolutely.

Why does that spare healthy tissue at the expense of cancer cells?

That is a question I cannot answer. To be honest, nobody knows. We know that it works, but I want to make it very clear that we need more research to translate it completely to the clinic. It is true that if you either fractionate in space or compress in time, normal tissue is much more resistant, while the effect on the tumour is approximately the same, allowing you to increase the dose without harming the patient. The problem is that the data are still controversial.

So you would say that it is not yet scientifically established that the FLASH effect is real?

There is an overwhelming amount of evidence for the strong sparing of normal tissue at specific sites, especially for the skin and for the brain. But, for example, for gastrointestinal tumours the data is very controversial. Some data show no effect, some data show a protective effect, and some data show an increased effectiveness of FLASH. We cannot generalise.

Is it surprising that the effect depends on the tissue?

In medicine this is not so strange. The brain and the gut are completely different. In the gut, you have a lot of cells that are quickly duplicating, while in the brain, you almost have the same number of neurons that you had when you were a teenager – unfortunately, there is not much exchange in the brain.

So, your frontier at GSI is FLASH with neon ions. Would you argue that microbeams are equally promising?

Absolutely, yes, though millibeams more so than microbeams, because microbeams are extremely difficult to go into clinical translation. In the micron region, any kind of movement will jeopardise your spatial fractionation. But if you have millimetre spacing, then this becomes credible and feasible. You can create millibeams using a grid. Instead of having one solid beam, you have several stripes. If you use heavier ions, they don’t scatter very much and remain spatially fractionated. There is mounting evidence that fractionated irradiation of the tumour can elicit an immune response and that these immune cells eventually destroy the tumour. Research is still ongoing to understand whether it’s better to irradiate with a spatial fractionation of 1 millimetre or to only radiate the centre of the tumour, allowing the immune cells to migrate and destroy the tumour.

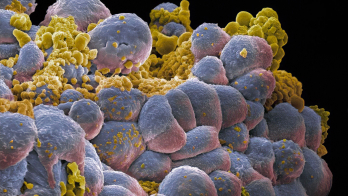

What’s the biology of the body’s immune response to a tumour?

To become a tumour, a cell has to fool the immune system, otherwise our immune system will destroy it. So, we are desperately trying to find a way to teach the immune system to say: “look, this is not a friend – you have to kill it, you have to destroy it.” This is immunotherapy, the subject of the Nobel Prize in medicine in 2018 and also related to the 2025 Nobel Prize in medicine on regulation of the immune system. But these drugs don’t work for every tumour. Radiotherapy is very useful in this sense, because you kill a lot of cells, and when the immune system sees a lot of dead cells, it activates. A combination of immunotherapy and radiotherapy is now being used more and more in clinical trials.

You also mentioned radioactive ion beams and the simultaneous acceleration of carbon and helium ions. Why are these approaches advantageous?

The two big problems with particle therapy are cost and range uncertainty. Having energy deposition concentrated at the Bragg peak is very nice, but if it’s not in the right position, it can do a lot of damage. Precision is therefore much more important in particle therapy than in conventional radiotherapy, as X-rays don’t have a Bragg peak – even if the patient moves a little bit, or if there is an anatomical change, it doesn’t matter. That’s why many centres prefer X-rays. To change that, we are trying to create ways to see the beam while we irradiate. Radioactive ions decay while they deposit energy in the tumour, allowing you to see the beam using PET. With carbon and helium, you don’t see the carbon beam, but you see the helium beam. These are both ways to visualise the beam during irradiation.

How significantly does radiation therapy improve human well-being in the world today?

When I started to work in radiation therapy at Berkeley, many people were telling me: “Why do you waste your time in radiation therapy? In 10 years everything will be solved.” At that time, the trend was gene therapy. Other trends have come and gone, and after 35 years in this field, radiation therapy is still a very important tool in a multidisciplinary strategy for killing tumours. More than 50% of cancer patients need radiotherapy, but, even in Europe, it is not available to all patients who need it.

Accelerator and detector physicists have to learn to speak the language of the non-specialist

What are the most promising initiatives to increase access to radiotherapy in low- and middle-income countries?

Simply making the accelerators cheaper. The GDP of most countries in Africa, South America and Asia is also steadily increasing, so you can expect that – let’s say – in 20 or 30 years from now, there will be a big demand for advanced medical technologies in these countries, because they will have the money to afford it.

Is there a global shortage of radiation physicists?

Yes, absolutely. This is true not only for particle therapy, which requires a high number of specialists to maintain the machine, but also for conventional X-ray radiotherapy with electron linacs. It’s also true for diagnostics because you need a lot of medical physicists for CT, PET and MRI.

What is your advice to high-energy physicists who have just completed a PhD or a postdoc, and want to enter medical physics?

The next step is a specialisation course. In about four years, you will become a specialised medical physicist and can start to work in the clinics. Many who take that path continue to do research alongside their clinical work, so you don’t have to give up your research career, just reorient it toward medical applications.

How does PTCOG exert leadership over global research and development?

The Particle Therapy Co-Operative Group (PTCOG) is a very interesting association. Every particle-therapy centre is represented in its steering committee. We have two big roles. One is research, so we really promote international research in particle therapy, even with grants. The second is education. For example, Spain currently has 11 proton therapy centres under construction. Each will need maybe 10 physicists. PTCOG is promoting education in particle therapy to train the next generation of radiation-therapy technicians and medical oncologists. It’s a global organisation, representing science worldwide, across national and continental branches.

Do you have a message for our community of accelerator physicists and detector physicists? How can they make their research more interdisciplinary and improve the applications?

Accelerator physicists especially, but also detector physicists, have to learn to speak the language of the non-specialist. Sometimes they are lost in translation. Also, they have to be careful not to oversell what they are doing, because you can create expectations that are not matched by reality. Tabletop laser-driven accelerators are a very interesting research topic, but don’t oversell them as something that can go into the clinics tomorrow, because then you create frustration and disappointment. There is a similar situation with linear accelerators for particle therapy. Since I started to work in this field, people have been saying “Why do we use circular accelerators? We should use linear accelerators.” After 35 years, not a single linear accelerator has been used in the clinics. There must also be a good connection with industry, because eventually clinics buy from industry, not academia.

Are there missed opportunities in the way that fundamental physicists attempt to apply their research and make it practically useful with industry and medicine?

In my opinion, it should work the other way around. Don’t say “this is what I am good at”; ask the clinical environment, “what do you need?” In particle therapy, we want accelerators that are cheaper and with a smaller footprint. So in whatever research you do, you have to prove to me that the footprint is smaller, and the cost lower.

Do forums exist where medical doctors can tell researchers what they need?

PTCOG is definitely the right place for that. We keep medicine, physics and biology together, and it’s one of the meetings with the highest industry participation. All the industries in particle therapy come to PTCOG. So that’s exactly the right forum where people should talk. We expect 1500 people at the next meeting, which will take place in Deauville, France, from 8 to 13 June 2026, shortly after IPAC.

Are accelerator physicists welcome to engage in PTCOG even if they’ve not previously worked on medical applications?

Absolutely. This is something that we are missing. Accelerator physicists mostly go to IPAC but not to PTCOG. They should also come to PTCOG to speak more with medical physicists. I would say that PTCOG is 50% medical physics, 30% medicine and 20% biology. So, there are a lot of medical physicists, but we don’t have enough accelerator physicists and detector physicists. We need more particle and nuclear physicists to come to PTCOG to see what the clinical and biology community want, and whether they can provide something.

Do you have a message for policymakers and funding agencies about how they can help push forward research in radiotherapy?

Unfortunately, radiation therapy and even surgery are wrongly perceived as old technologies. There is not much investment in them, and that is a big problem for us. What we miss is good investment at the level of cooperative programmes that develop particle therapy in a collaborative fashion. At the moment, it’s becoming increasingly difficult. All the money goes into prevention and pharmaceuticals for immunotherapy and targeted therapy, and this is something that we are trying to revert.

Are large accelerator laboratories well placed to host cooperative research projects?

Both GSI and CERN face the same challenge: their primary mission is nuclear and particle physics. Technological transfer is fine, but they may jeopardise their funding if they stray too far from their primary goal. I believe they should invest more in technological transfer, lobbying their funding agencies to demonstrate that there is a translation of their basic science into something that is useful for public health.

How does your research in particle therapy transfer to astronaut safety?

Particle therapy and space-radiation research have a lot in common. They use the same tools and there are also a lot of overlapping topics, for example radiosensitivity. One patient is more sensitive, one patient is more resistant, and we want to understand what the difference is. The same is true of astronauts – and radiation is probably the main health risk for long-term missions. Space is also a hostile environment in terms of microgravity and isolation, but here we understand the risks, and we have countermeasures. For space radiation, the problem is that we don’t understand the risk very well, because the type of radiation is so exotic. We don’t have that type of radiation on Earth, so we don’t know exactly how big the risk is. Plus, we don’t have effective countermeasures, because the radiation is so energetic that shielding will not be enough to protect the crews effectively. We need more research to reduce the uncertainty on the risk, and most of this research is done in ground-based accelerators, not in space.

Radiation therapy is probably the best interdisciplinary field that you can work in

I understand that you’re even looking into cryogenics…

Hibernation is considered science fiction, but it’s not science fiction at all – it’s something we can recreate in the lab. We call it synthetic torpor. This can be induced in animals that are non-hibernating. Bears and squirrels hibernate; humans and rats don’t, but we can induce it. And when you go into hibernation, you become more radioresistant, providing a possible countermeasure to radiation exposure, especially for long missions. You don’t need much food, you don’t age very much, metabolic processes are slowed down, and you are protected from radiation. That’s for space. This could also be applied to therapy. Imagine you have a patient with multiple metastasis and no hope for treatment. If you can induce synthetic torpor, all the tumours will stop, because when you go into a low temperature and hibernation, the tumours don’t grow. This is not the solution, because when you wake the patient up, the tumours will grow again, but what you can do is treat the tumours while you are in hibernation, while healthy tissue is more radiation resistant. The number of research groups working on this is low, so we’re quite far from considering synthetic torpor for spaceflight or clinical trials for cancer treatment. First of all, we have to see how long we can keep an animal in synthetic torpor. Second, we should translate into bigger animals like pigs or even non-human primates.

In the best-case scenario, what can particle therapy look like in 10 years’ time?

Ideally, we should probably at least double the amount of particle-therapy centres that are now available, and expand into new regions. We finally have a particle-therapy centre in Argentina, which is the first one in South America. I would like to see many more in South America and in Africa. I would also like to see more centres that try to tackle tumours where there is no treatment option, like glioblastoma or pancreatic cancer, where the mortality is the same as the incidence. If we can find ways to treat such cancers with heavy ions and give hope to these patients, this would be really useful.

Is there a final thought that you’d like to leave with readers?

Radiation therapy is probably the best interdisciplinary field that you can work in. It’s useful for society and it’s intellectually stimulating. I really hope that big centres like CERN and GSI commit more and more to the societal benefits of basic research. We need it now more than ever. We are living in a difficult global situation, and we have to prove that when we invest money in basic research, this is very well invested money. I’m very happy to be a scientist, because in science, there are no barriers, there is no border. Science is really, truly international. I’m an advocate of saying scientific collaboration should never stop. It didn’t even stop during the Cold War. At that time, the cooperation between East and West at the scientist level helped to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons. We should continue this. We don’t have to think that what is happening in the world should stop international cooperation in science: it eventually brings peace.