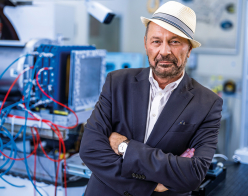

Francesca Luoni advises early-career researchers on how to shield their career while transitioning from research to engineering, and back again.

When Francesca Luoni logs on each morning at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Virginia, she’s thinking about something few of us ever consider: how to keep astronauts safe from the invisible hazards of space radiation. As a research scientist in the Space Radiation Group, Luoni creates models to understand how high-energy particles from the Sun and distant supernovae interact with spacecraft structures and the human body – work that will help future astronauts safely travel deeper into space.

But Luoni is not a civil servant for NASA. She is contracted through the multinational engineering firm Analytical Mechanics Associates, continuing a professional slingshot from pure research to engineering and back again. Her career is an intriguing example of how to balance research with industrial engagement – a holy grail for early-career researchers in the late 2020s.

Leveraging expertise

Luoni’s primary aim is to optimise NASA’s Space Radiation Cancer Risk Model, which maps out the cancer incidence and mortality risk for astronauts during deep-space missions, such as NASA’s planned mission to Mars. To make this work, Luoni’s team leverages the expertise of all kinds of scientists, from engineers, statisticians and physicists, to biochemists, epidemiologists and anatomists.

“I’m applying my background in radiation physics to estimate the cancer risk for astronauts,” she explains. “We model how cosmic rays pass through the structure of a spacecraft, how they interact with shielding materials, and ultimately, what reaches the astronauts and their tissues.”

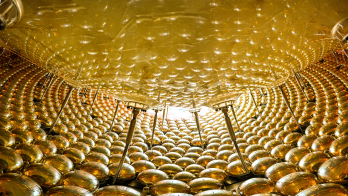

Before arriving in Virginia early this year, Luoni had already built a formidable career in space-radiation physics. After a physics PhD in Germany, she joined the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research, where she spent long nights at particle accelerators testing new shielding materials for spacecraft. “We would run experiments after the medical facility closed for the day,” she says. “It was precious work because there are so few facilities worldwide where you can acquire experimental data on how matter responds to space-like radiation.”

Her experiments combined experimental measurement data with Monte Carlo simulations to compare model predictions with reality – skills she honed during her time in nuclear physics that she still uses daily at NASA. “Modelling is something you learn gradually, through university, postgrads and research,” says Luoni. “It’s really about understanding physics, maths, and how things come together.”

In 2021 she accepted a fellowship in radiation protection at CERN. The work was different from the research she’d done before. It was more engineering-oriented, ensuring the safety of both scientists and surrounding communities from the intense particle beams of the LHC and SPS. “It may sound surprising, but at CERN the radiation is far more energetic than we see in space. We studied soil and water activation, and shielding geometries, to protect everyone on site. It was much more about applied safety than pure research.”

Luoni’s path through academia and research was not linear, to say the least. From being an experimental physicist collecting data at GSI, to working as an engineer and helping physicists conduct their own experiments at CERN, Luoni is excited to be diving back into pure research, even if it wasn’t her initially intended field.

Despite her industry–contractor title, Luoni’s day-to-day work at NASA is firmly research-driven. Most of her time is spent refining computational models of space-radiation-induced cancer risk. While the coding skills she honed at CERN apply to her role now, Luoni still experienced a steep learning curve when transitioning to NASA.

“I am learning biology and epidemiology, understanding how radiation damages human tissues, and also deepening my statistics knowledge,” she says. Her team codes primarily in Python and MATLAB, with legacy routines in Fortran. “You have to be patient with Fortran,” she remarks. “It’s like building with tiny bricks rather than big built-in functions.”

Luoni is quick to credit not just the technical skills but the personal resilience gained from moving between countries and disciplines. Born in Italy, she has worked in Germany, Switzerland and now the US. “Every move teaches you something unique,” she says. “But it’s emotionally demanding. You face bureaucracy, new languages, distance from family and friends. You need to be at peace with yourself, because there’s loneliness too.”

Bravery and curiosity

But in the end, she says, it’s worth the price. Above all, Luoni counsels bravery and curiosity. “Be willing to step out of your comfort zone,” she says. “It takes strength to move to a new country or field, but it’s worth it. I feel blessed to have experienced so many cultures and to work on something I love.”

While she encourages travel, especially at the PhD and postdoc stages in a researcher’s career, Luoni advises caution when presenting your experience on applications. Internships and shorter placements are welcome, but employers want to see that you have stayed somewhere long enough to really understand and harness that company’s training.

“Moving around builds a unique skill set,” she says. “Like it or not, big names on your CV matter – GSI, CERN, NASA – people notice. But stay in each place long enough to really learn from your mentors, a year is the minimum. Take it one step at a time and say yes to every opportunity that comes your way.”

Luoni had been looking for a way to enter space-research throughout her career, building up a diverse portfolio of skills throughout her various roles in academia and engineering. “Follow your heart and your passions,” she says. “Without that, even the smartest person can’t excel.”