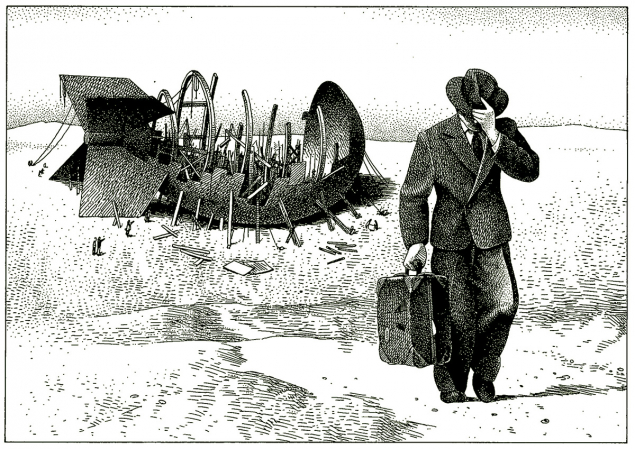

Subatomic physics has shaped both the conduct of war and the treatment of cancer. Joseph Rotblat, who left the Manhattan Project on moral grounds and later advanced radiotherapy, embodies this dual legacy, as his biographer Andrew Brown recounts.

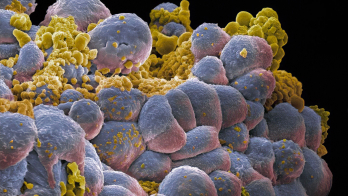

Joseph Rotblat’s childhood was blighted by the destruction visited on Warsaw, first by the Tsarist Army, followed by the Central Powers and completed by the Red Army from 1918 to 1920. His father’s successful paper-importing business went bankrupt in 1914, and the family became destitute. After a short course in electrical engineering, Joseph and a teenaged friend became jobbing electricians. A committed autodidact, Rotblat found his way into the Free University, where he studied physics under Ludwik Wertenstein. Wertenstein had worked with Marie Skłodowska-Curie in Paris and was the chief of the Radiological Institute in Warsaw as well as teaching at the Free University. He was the first to recognise Rotblat’s brilliance and retained him as a researcher at the Institute. Rotblat’s main research was neutron-induced artificial radioactivity: he was among the first to induce cobalt-60, which became a standard source in radiotherapy machines before reliable linear accelerators were available.

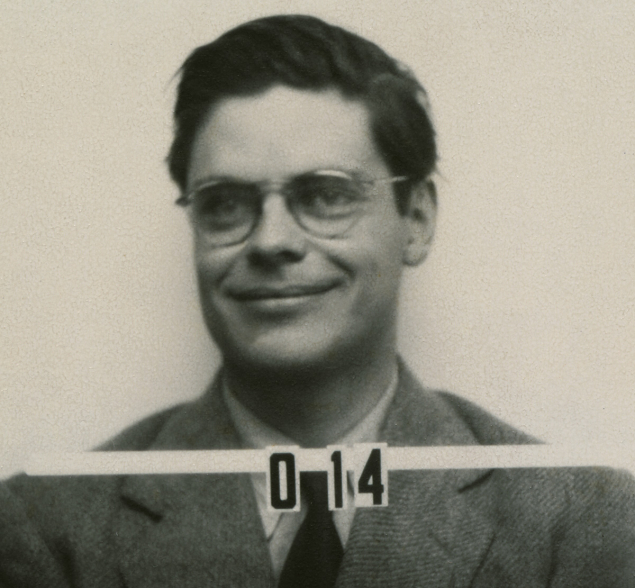

Chadwick described Rotblat as “very intelligent and very quick”

By the late 1930s, Rotblat had published more than a dozen papers, some in English journals after translation by Wertenstein; the name Rotblat was becoming known in neutron physics. The professor regarded him as the likely next head of the Radiological Institute and thought he should prepare by working outside Poland. Rotblat wanted to gain experience of the cyclotron and, although he could have joined the Joliot–Curie group in Paris, elected to go to Liverpool where James Chadwick was overseeing a machine expected to produce a proton beam within months. He arrived in Liverpool in April 1939 and was shocked by the city’s filth. He also found the scouse dialect of its citizens incomprehensible. Despite the trying circumstances, Rotblat soon impressed Chadwick with his experimental skill and was rewarded with a prestigious fellowship. Chadwick wrote to Wertenstein in June describing Rotblat as “very intelligent and very quick”.

Brimming with enthusiasm

Chadwick had formed a long-distance friendship with Ernest Lawrence, the cyclotron’s inventor, who kept him apprised of developments in Berkeley. At the time of Rotblat’s arrival, Lawrence was brimming with enthusiasm about the potential of neutrons and radioactive isotopes from cyclotrons for medical research, especially in cancer treatment. Chadwick hired Bernard Kinsey, a Cambridge graduate who spent three years with Lawrence, to take charge of the Liverpool cyclotron, and he befriended Rotblat. Liverpool had limited funding: Chadwick complained to Lawrence that the money “this laboratory has been running on in the past few years – is less than some men spend on tobacco.” Chadwick served on a Cancer Commission in Liverpool under the leadership of Lord Derby, which planned to bring cancer research to the Liverpool Radium Institute using products from the cyclotron.

The small stipend from the Oliver Lodge fellowship encouraged Rotblat to return to Warsaw in August 1939 to collect his wife, Tola, and bring her to England. She was recovering from acute appendicitis; her doctors persuaded Joseph that she was not fit to travel. So he returned alone on the last train allowed to pass through Berlin before the Germans attacked Poland once more. Tola wrote her last letter to Joseph in December 1939. While he was in Warsaw, Rotblat confided in Wertenstein about his belief that a uranium fission bomb was feasible using fast neutrons, and he repeated this argument to Chadwick when he returned to Liverpool. Chadwick eventually became the leader of the British contingent on the Manhattan Project and arranged for Rotblat to come to Los Alamos in 1944 while remaining a Polish citizen. Rotblat worked in Robert Wilson’s cyclotron group and survived a significant radiation accident, receiving an estimated dose of 1.5 J/kg to his upper torso and head. The circumstances of his leaving the project in December 1944 were far more complicated than the moralistic account he wrote in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 40 years later, but no less noble.

Tragedy and triumph

As Chadwick wrote to Rotblat in London, he saw “very obvious advantages” for the future of nuclear physics in Britain from Rotblat’s return to Liverpool. For one thing, “Rotblat has a wider experience on the cyclotron than anyone now in England,” and he also possessed “a mass of information on the equipment used in Project Y [Los Alamos] and Chicago.” Chadwick had two major roles in mind for Rotblat. One was to revitalise the depleted Liverpool department and to stimulate cyclotron research in England; and the second to collate the detailed data on nuclear physics brought by British scientists returning from the Manhattan Project. In 1945, Rotblat discovered that six members of his family had miraculously survived the war in Poland, but tragically not Tola. His state of despair deepened after the news of the atomic bombs being used against Japan: he knew about the possibility of a hydrogen bomb, and remembered conversations with Niels Bohr in Los Alamos about the risks of a nuclear arms race. He made two resolutions: to campaign against nuclear weapons and to leave academic nuclear physics and become a medical physicist to use his scientific knowledge for the direct benefit of people.

When Chadwick returned to Liverpool from the US, he found the department in a much better state than he expected. The credit for this belonged largely to Rotblat’s leadership; Chadwick wrote to Lawrence praising his outstanding ability, combined with a truly remarkable concern for the staff and students. Chadwick and Rotblat then agreed to build a synchrocyclotron in Liverpool. Rotblat selected the abandoned crypt of an unbuilt Catholic cathedral as the best site, since the local topography would provide some radiation protection. The post-war shortages, especially of steel, made this an extremely ambitious project. Rotblat presented a successful application for the largest university grant to the Department of Science and Industrial Research, and despite design and construction problems resulting in spiralling costs, the machine was in active research use from 1954 to 1968.

With the encouragement of physicians at Liverpool Royal Infirmary, Rotblat started to dabble in nuclear medicine to image thyroid glands and treat haematological disorders. In 1949 he saw an advert for the chair in physics at the Medical College of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital (Bart’s) in London and applied. While Rotblat was easily the most accomplished candidate, there was a long delay in his appointment on spurious grounds, such as being over-qualified to teach physics to medical students, likely to be a heavy consumer of research funds and xenophobia. Bart’s was a closed, reactionary institution. There was a clear division between the Medical College, with its links to London University, and the hospital, where the post-war teaching was suboptimal as it struggled to recover from the war and adjusted reluctantly to the new National Health Service (NHS). The Medical College, in Charterhouse Square, was severely bombed in the Blitz and the physics department completely destroyed. Rotblat attempted to thwart his main opponent, the dean (described as “secretive and manipulative” in one history), by visiting the hospital and meeting senior clinicians and governors. There was also a determined effort, orchestrated by Chadwick, to retain him in the ranks of nuclear physicists.

When I interviewed Rotblat in 1994, he told me that Chadwick’s final tactic was to tell him that he was close to being elected as a fellow of the Royal Society, but if he took the position at Bart’s, it would never happen. Rotblat poignantly observed: “He was right.” I mentioned this to Lorna Arnold, the nuclear historian, who thought it was a shame. She said she would take it up with her friend Rudolf Peierls. Despite being in poor health, Peierls vowed to correct this omission, and the next year the Royal Society elected Rotblat a fellow at the age of 86.

Full-time medical physicist

Rotblat’s first task at Bart’s, when he finally arrived in 1950, was to prepare a five-year departmental plan: a task he was well-qualified for after his experience with the synchrocyclotron in Liverpool. With wealthy, centuries-old hospitals such as Bart’s allowed to keep their endowments after the advent of the NHS, he also became an active committee member for the new Research Endowment Fund that provided internal grants and hired research assistants. The physics department soon collaborated with the biochemistry, pharmacology and physiology departments that required radioisotopes for research. He persuaded the Medical College to buy a 15 MV linear accelerator from Mullard, an English electronics company, which never worked for long without problems.

Rotblat resolved to campaign against nuclear weapons and use his scientific knowledge for the direct benefit of people

During his first two years, in addition to the radioisotope work, he studied the passage of electrons through biological tissue and the energy dissipation of neutrons in tissue – the 1950s were a golden age for radiobiology in England, and Rotblat forged close relationships with Hal Gray and his group at the Hammersmith Hospital. In the mid-1950s, he was approached by Patricia Lindop, a newly qualified Bart’s physician who had also obtained a first-class degree in physiology. Lindop had a five-year grant from the Nuffield Foundation to study ageing and, after discussions with Rotblat, it was soon arranged that she would study the acute and long-term effects of radiation in mice at different ages. This was a massive, prospective study that would eventually involve six research assistants and a colony of 30,000 mice. Rotblat acted as the supervisor for her PhD, and they published multiple papers together. In terms of acute death (within 30 days of a high, whole-body dose), she found that mice that were one-day old at exposure could tolerate the highest doses, whereas four-week-old mice were the most vulnerable. The interpretation of long-term effects was much less clearcut and provoked major disagreements within the radiobiology community. In a 1994 letter, Rotblat mused on the number of Manhattan Project scientists still alive: “According to my own studies on the effects of radiation on lifespan, I should have been dead a long time, having received a sub-lethal dose in Los Alamos. But here I am, advocating the closure of Los Alamos, Livermore and Sandia, instead of promoting them as health resorts!”

In 1954, the US Bravo test obliterated the Bikini atoll and layered a Japanese fishing boat (Lucky Dragon No. 5) that was outside the exclusion zone in the South Pacific with radioactive dust. American scientists realised that the weapon massively exceeded its designed yield, and there was an unconvincing attempt to allay public fear. Rotblat was invited onto BBC’s flagship current-affairs programme, Panorama, to explain to the public the difference between the original fission bombs and the H-bomb. His lucid delivery impressed Bertrand Russell, a mathematical philosopher and a leading pacifist in World War I, who also spoke on Panorama. The two became close friends. When Rotblat went to a radiobiology conference a few months later, he met a Japanese scientist who had analysed the dust recovered from Lucky Dragon No. 5. The dust was comprised of about 60% rare-earth isotopes, leading Rotblat to believe that most of the explosive energy was due to fission not fusion. He wrote his own report, not based on any inside knowledge and despite official opposition, concluding this was a fission–fusion–fission bomb and that his TV presentation had underestimated its power by orders of magnitude. Rotblat’s report became public just as the British Cabinet decided in secret to develop thermonuclear weapons. The government was concerned that the Americans would view this as another breach of security by an ex-Manhattan Project physicist. Rotblat’s reputation as a man of the political left grew within the conservative institution of Bart’s.

Russell made a radio address at the end of 1954 to address the global existential threat posed by thermonuclear weapons and urged the public to “remember your humanity and forget the rest”. Six months later, Russell announced the Russell–Einstein Manifesto with Rotblat as one of the signatories, and relied upon by Russell to answer questions from the press. The first Pugwash conference followed in 1957 with Rotblat as a prominent contributor. His active involvement, closely supported by Lindop, would last for the rest of his life, as he encouraged communication across the East–West divide and pushed for international arms control agreements. Much of this work took place in his office at Bart’s. Rotblat and the Pugwash conference then shared the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize.

Further reading

A Brown 2012 Keeper of the Nuclear Conscience: The Life and Work of Joseph Rotblat Oxford University Press.